Our “Plant This, Not That” series aims to help you find a native plant to use instead of or to replace the invasive species in your yard. These plants can not only provide the same look and texture, but also, similar features and growing habits, all while providing critical habitat for native wildlife.

When visiting the garden center, finding native alternatives to the non-native (and typically invasive) species can be a challenge. Help improve native plant supply by asking for native plant species!

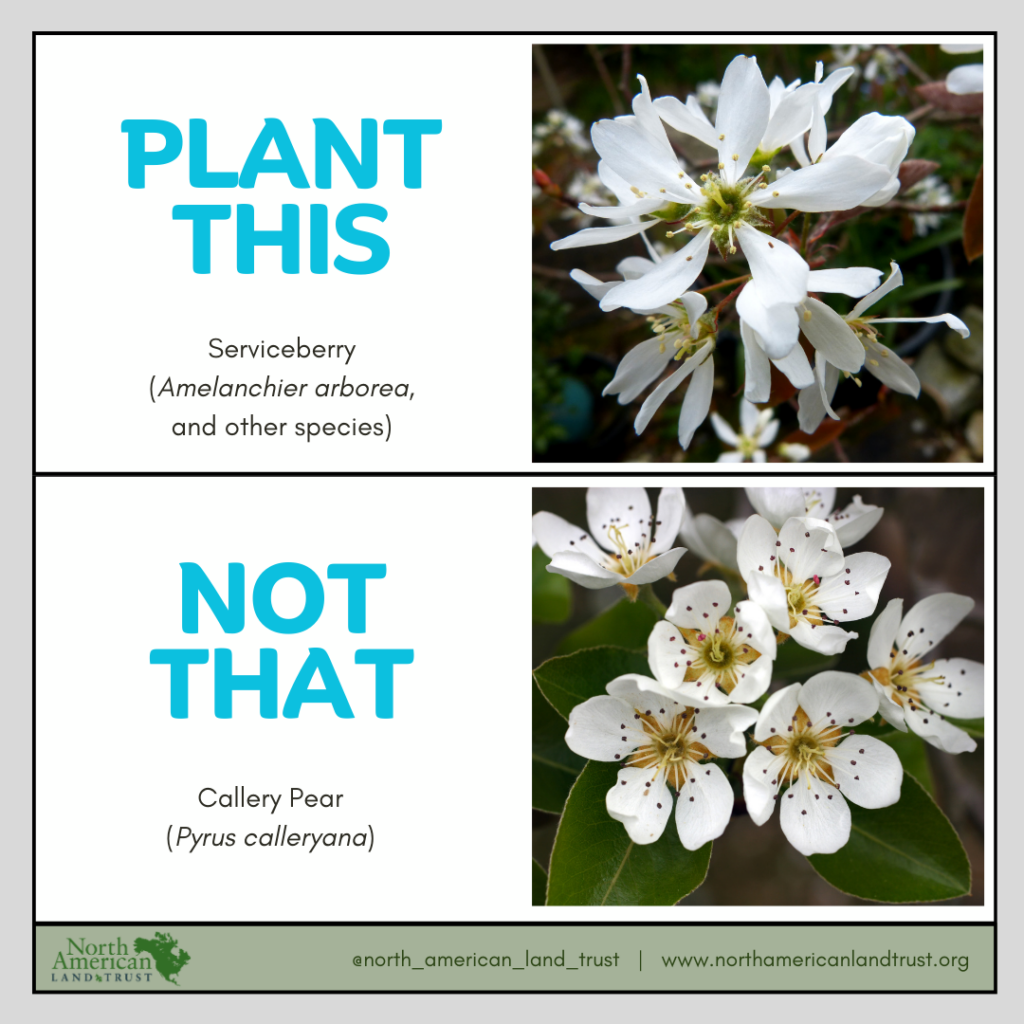

Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana), of the Rose family, was imported in the early 1900s and has been heavily planted since. The species is naturalized throughout the East and Midwest, particularly in disturbed habitats forming dense thickets which can crowd out natives. This plant is a prime example of a “sterile” species not meant to reproduce in the wild, but cross-pollination among the 20 or more cultivars have created fertile fruit which spreads, primarily through bird droppings, making it difficult to eradicate.

A great and overlooked alternative to Callery Pear is North America’s native Serviceberries (Amelanchier sp.). The flowers are very similar in color and shape, are fragrant, and can grow in a range of sun and soil conditions. They feed many native insects and the berries are loved by wildlife. Native hawthorns and native crabapples, plums, or cherries, also make great substitutes if you are having a hard time finding a Serviceberry suitable for your area.

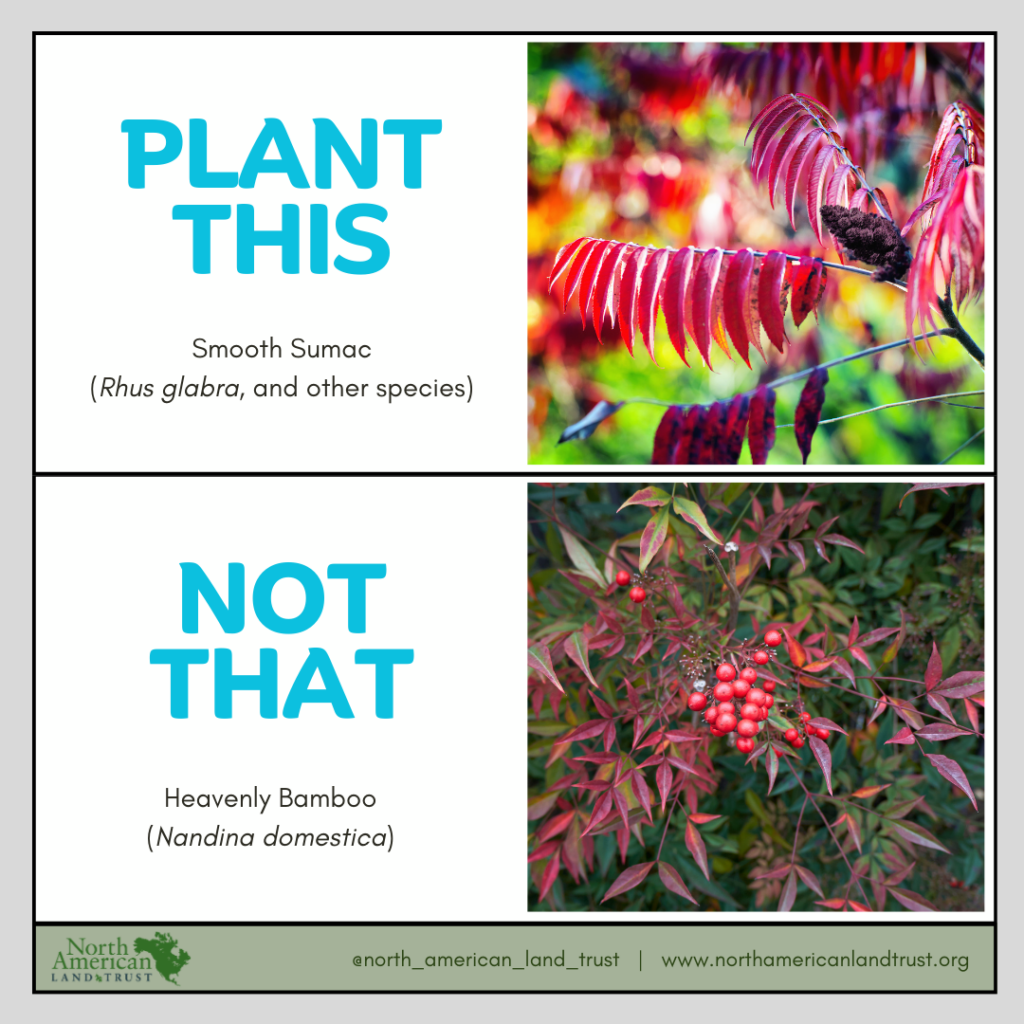

Heavenly Bamboo (Nandina domestica) is a widespread invasive species throughout much of the South and Southeast, creeping towards the Northeast, where it commonly escapes planted areas. Its fruits are poisonous, but birds and small mammals can eat them in low quantities, and therefore disperse them in natural areas through their feces. Otherwise, this species provides no benefit for wildlife.

Native Sumac (Rhus sp.), however, makes a fantastic alternative to heavenly bamboo as it has red berries that persist all winter long, beautiful flowers in the spring and summer, and stunning red foliage in the fall. Birds and animals alike love the fruit and for humans, the fruit of Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) can be used as a spice or added to water to make a natural lemonade. The species also acts as a host plant for caterpillars like the Red-banded hairstreak butterfly. There are many native Sumac species meaning there is one perfect for your yard, climate, and region.

Winged Euonymus (Euonymus alatus) is a widespread invasive species throughout much of the East coast and Midwest, where it commonly escapes planted areas. Its fruits are eaten by birds and small mammals which is how they are easily dispersed into natural areas, through their feces. Otherwise, this species provides no benefit for wildlife in the form of a food plant for insects. It was first introduced in the 1860s as an ornamental and unfortunately, is still sold in states where it is not banned. They easily create dense thickets where it displaces all native species nearby.

Native Euonymus (aka wahoo or heart’s a bustin’) (Euonymus americanus), however, makes a fantastic alternative to winged burning bush as it has red berries that persist all winter long, diminutive but beautiful flowers in the spring and summer, and stunning red foliage in the fall. Birds and animals (like deer and rabbits) alike love the fruit and the species attracts a number of insects like bees and flies and is a host plant for caterpillars of the American Ermine Moth and the Long-horned beetle.

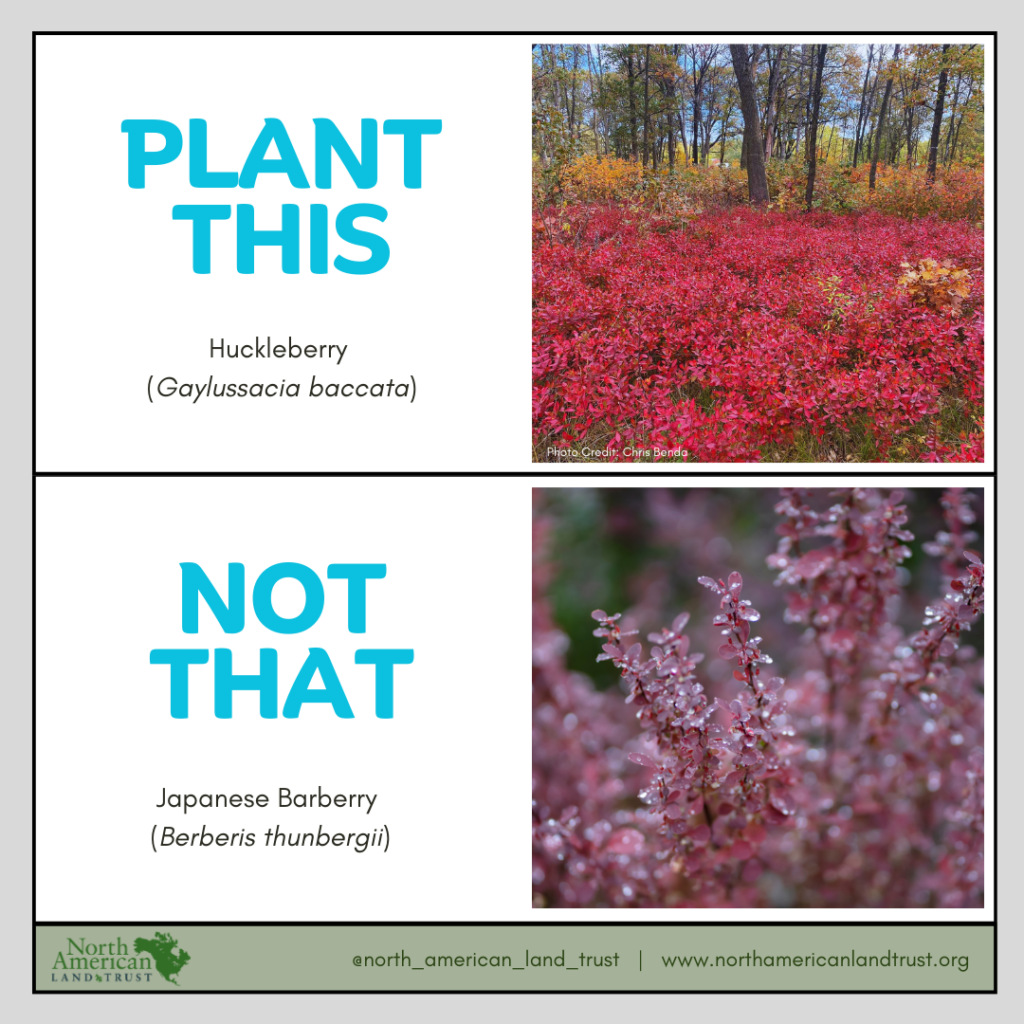

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is probably one of the most pernicious invasive species throughout the East coast and Midwest, where it commonly escapes planted areas. Its fruits are eaten by birds and small mammals and is easily dispersed into natural areas through their feces. Otherwise, this species provides no benefit for wildlife in the form of a food plant for insects. It was introduced in the 1870s as an ornamental hedgerow and is still sold in states where it is not banned. They easily create dense thickets where it displaces all native species nearby.

Native Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), however, is one of many native plants that make a fantastic alternative to barberry, as it produces diminuitive but beautiful flowers in the spring and summer and stunning red foliage in the fall. Birds, animals, and even humans love the fruit and the species attracts a number of insects like bees, syrphid flies, and butterflies including the endangered Karner Blue butterfly (Plebejus melissa samuelis). It is a host plant for the caterpillars of several moths including the decorated Owlet and the Huckleberry Eye-Spot.

Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is probably one of the most pernicious and well-known invasive species throughout the United States, among other non-native Lonicera species. Spreading by seed via birds who find the fruit attractive and edible, these plants quickly travel far and wide, creating extremely dense thickets that are difficult to eradicate. When removing honeysuckle, it is best to cut, stump treat with herbicide, and replace with a native shrub as soon as possible to prevent re-colonization.

There are a wide variety of native shrubs that can be used as a substitute for Honeysuckle, including flowering dogwoods, Aronia bush, buttonbush, american hazelnut, and various viburnum species. We have chosen Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius) as our “Plant This” species due to its wider range and similar foliage, flowers, and growth habit in a range of conditions. It has a beautifully textured bark for winter interest, large colorful blossoms, and red clusters of fruit in the fall.

To learn more about Bush Honeysuckle: . To learn more about our native Ninebark:

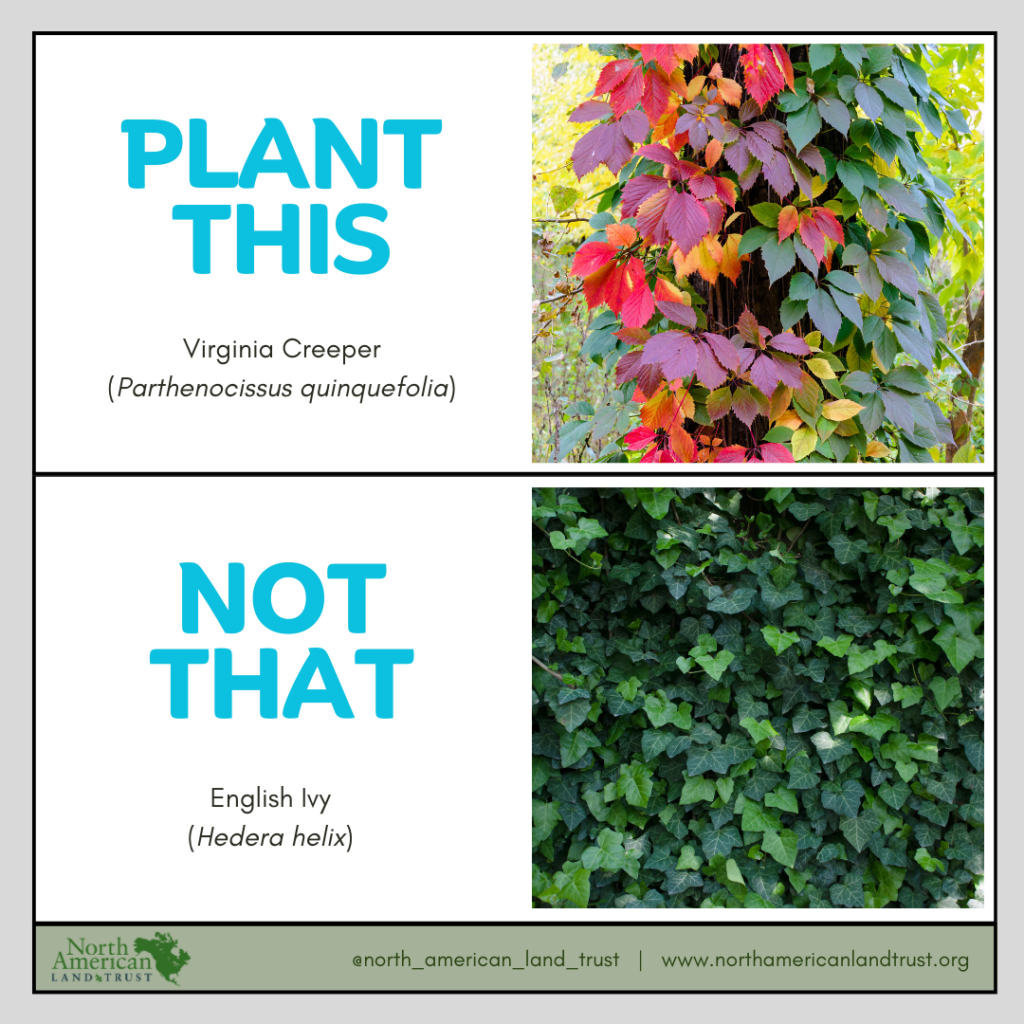

Most people throughout the Eastern and Western U.S. are familiar with English Ivy (Hedera helix), thanks to its notoriety as one of the most difficult invasive horticultural species to eradicate. It was introduced as an evergreen groundcover from Europe in the 1700s and unfortunately, continues to be sold as such. Unfortunately, it is an aggressive invader, choking out understory vegetation and enveloping native trees, causing them to decline for many years before dying. As it vines via underground runners and grows clonally, it can be extremely difficult to remove from the landscape.

A potential native groundcover or vining alternative is Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). It is related to grapes and while it is deciduous, not evergreen, it provides beautiful deep red foliage through fall and green foliage in the growing season and is tolerant of sun or shade. The fruits (toxic to humans) are enjoyed by birds and small mammals and the flowers attract insects.

Japanese Pachysandra (Pachysandra terminalis) is commonly planted in gardens throughout the East coast and Midwest, however, it can escape planted areas. Growing by rhizome, runners can spread quickly and is difficult to eradicate, easily crowding out native forest species by competing for light and soil resources.

Allegheny Spurge (Pachysandra procumbens) is distributed primarily throughout the Southeast, parts of the Midwest, and some of the East Coast, in zones 6 – 8. This species has a beautiful mottling on the foliage and is very attractive in the understory, especially shady areas. Flowers on both species are showy and fragrant and is an early nectar source for pollinators.

Unfortunately, these two species ranges don’t completely overlap and are not a direct substitute for each other. However, there are many other great native ground covers for your area if Allegheny Spurge is not in range for you. Some alternatives can include those in the links above.

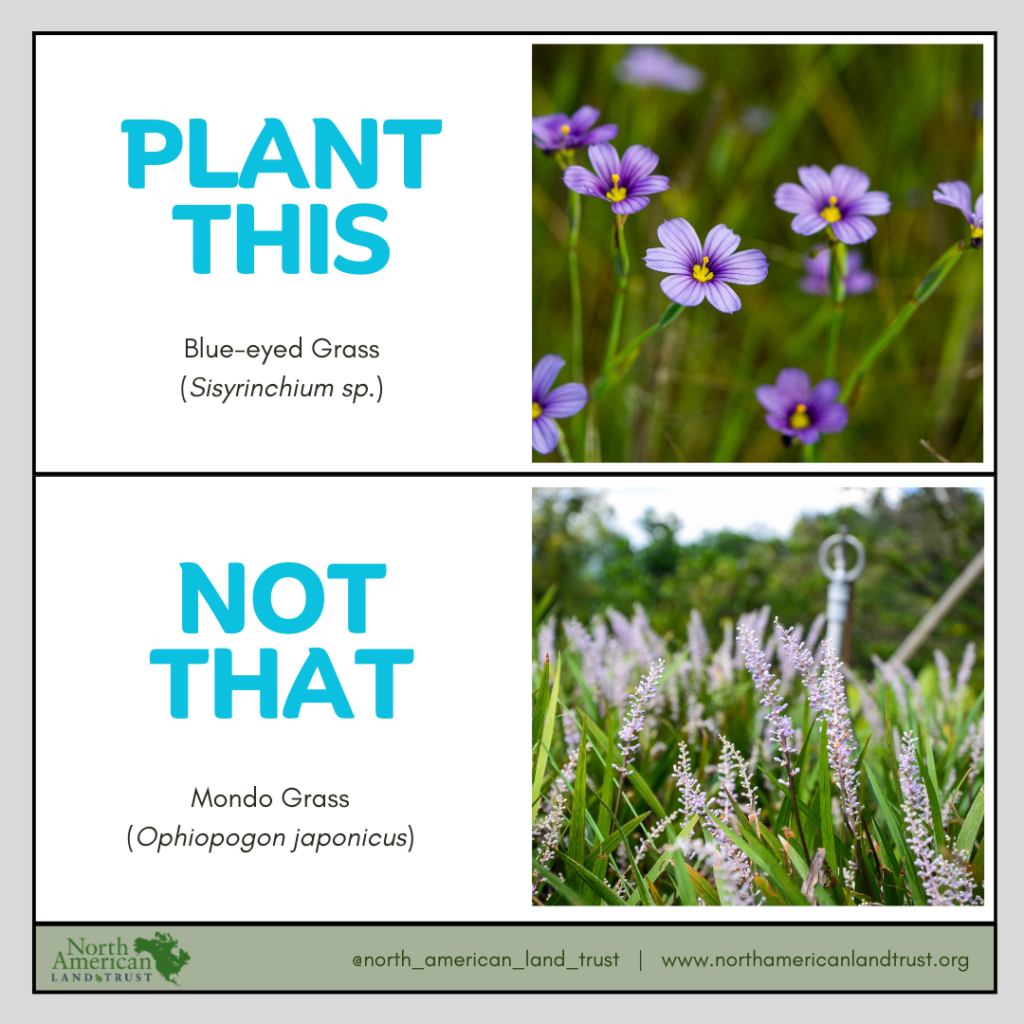

Mondo Grass (Ophiopogon japonicus) and Monkey Grass (Liriope muscari) are two commonly used plants for landscape edges and borders due to their ability to handle wear and tear, and their evergreen foliage, purple flowers, and small blue berries. Birds and other animals however often eat the non-toxic fruits, dispersing them to natural areas where they quickly grow and take over, crowding out native plant species.

A fantastic substitute are those in the genus Sisyrinchium, or the Blue-Eyed Grasses. These plants are not actually grasses, but they are related to Irises (Iridaceae). We did not pick a specific species to highlight as there are over 50 native species and bound to be one fit for your region. They are often evergreen, although die back in cold climates, and are hardy to a variety of soil conditions, producing clumps of sword-shaped leaves and then stunning small, but jewel colored blooms for much of the summer. The seeds are eaten by a variety of birds, including Wild Turkey.

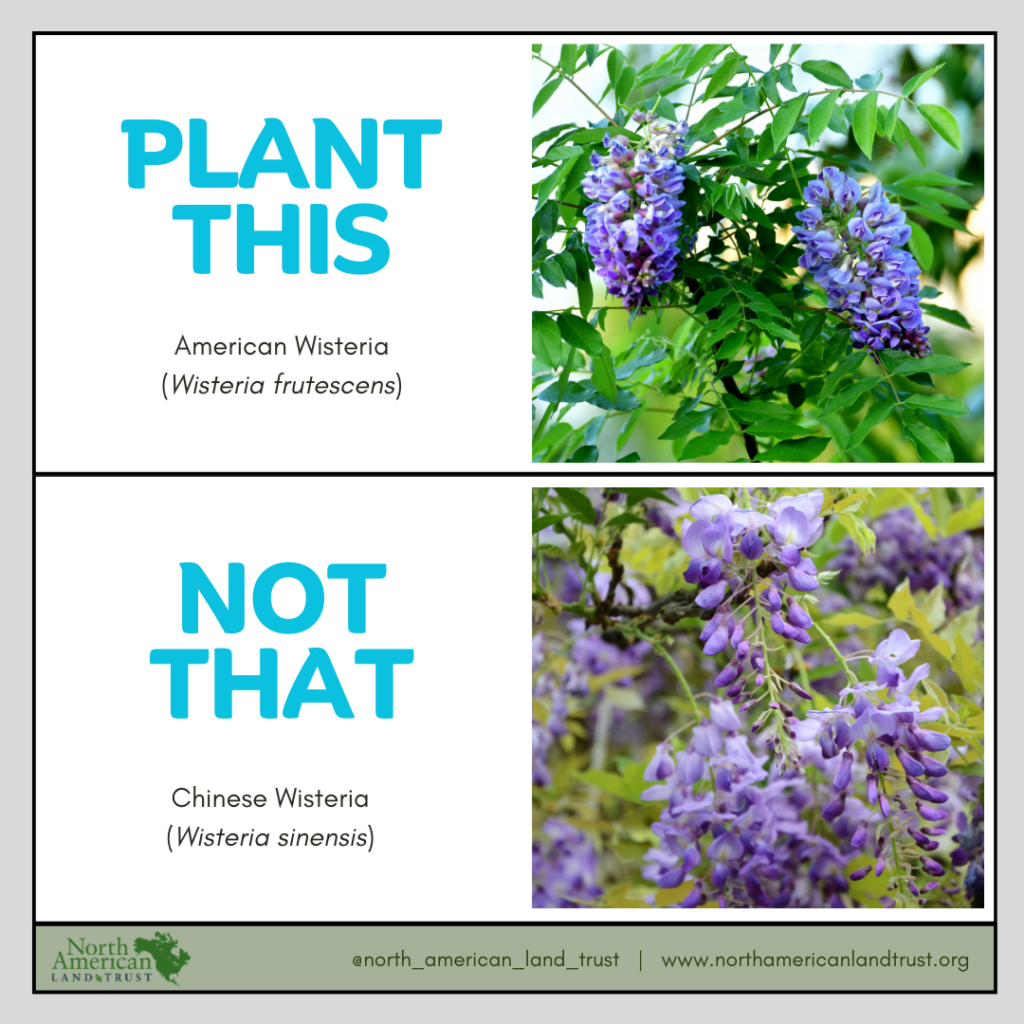

Wisteria is a stunning spring blooming vine with pinnate leaves and pendulous purple fragrant flowers, but did you know that most Wisteria you see is non-native? Chinese Wisteria (Wisteria sinensis) was introduced as an ornamental species in the early 1900s and is now found extensively throughout the Eastern U.S. and considered invasive in at least 19 states. The vines are exceptional climbers that can choke out native trees and vegetation, most commonly in disturbed areas like forest edges and rights-of-ways. They can easily spread by seed or by underground runners.

Fortunately, there is a lesser known but even more beautiful native Wisteria species, American Wisteria (Wisteria frutescens). Our native species is not only a nectar source for butterflies and native insects, but it is also the larval host for silver-spotted skipper butterflies.

Oregon Grape (Mahonia aquifolium) is often selected for its evergreen leaves, yellow flowers, and blueish fruits, however this species, native to British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, northern California and northern Idaho has spread throughout much of the Eastern United States. Outside its native range, has the ability to displace native vegetation as it is able to spread into colonies via underground runners. It often is spread via the fruits, which are occasionally eaten by birds.

American Holly (Ilex opaca) is an evergreen native, holding onto green waxy foliage long into the cold months of winter. The red berries held all winter long are a critical food source for native birds and wildlife, who can eat the otherwise toxic fruit, at a time where there is little available to eat. It is a great substitute for non-native fruiting trees in your own home landscape. The species range is throughout much of the Eastern United States.

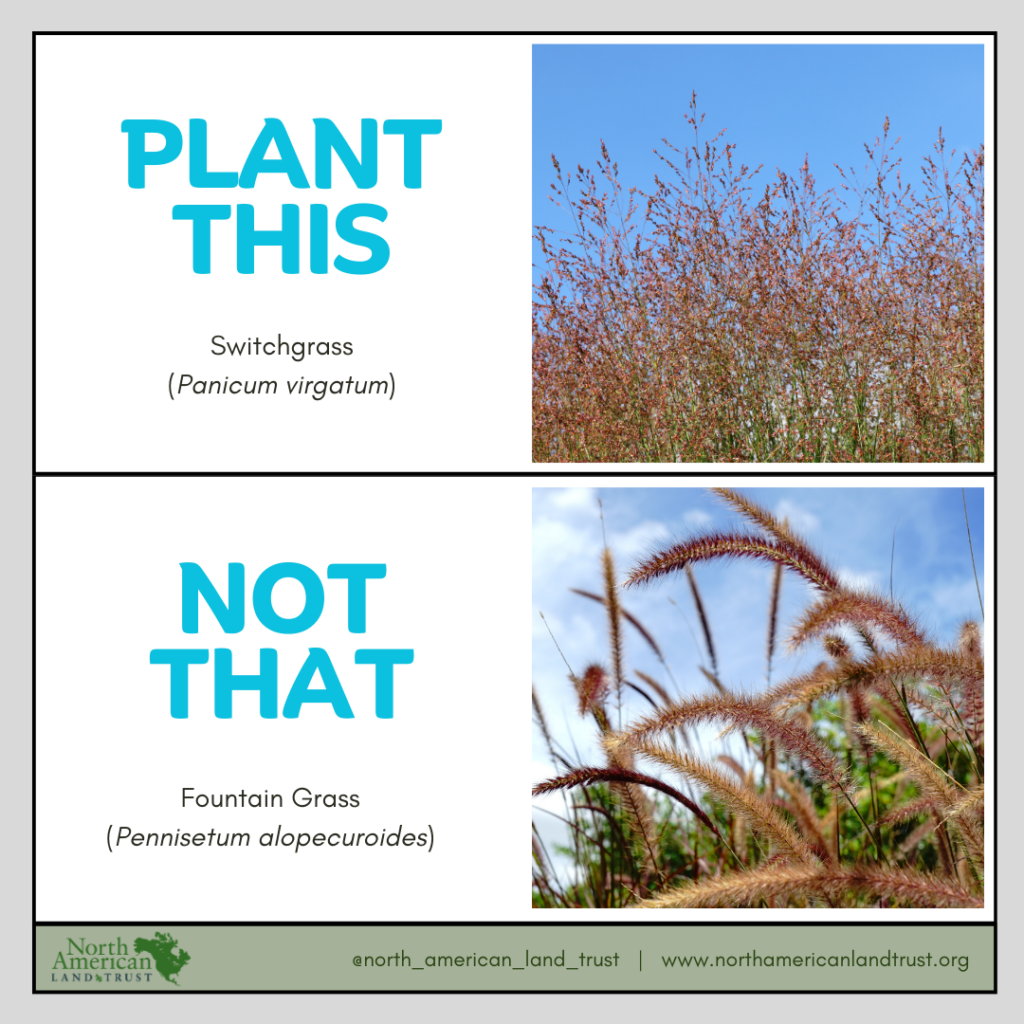

Chinese Fountain Grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides) is a hardy perennial grass often used for landscaping, sometimes as an annual in cold climates. It is considered an “emerging threat” as a potential invasive species after recent reports that it is escaping cultivation and naturalizing in NY, PA, IL, and AR. These grasses easily escape planted areas due to the abundance of wind blown seeds and can form dense stands that are difficult to eradicate.

There are a number of great native grasses that can be used as a substitute, including native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). Panic Grass is a great perennial grass substitute as it forms large clumps and produces purple lacy sprays of flowers and seeds. It is native to much of the East and Midwest United States and can handle a range of conditions, primarily dry or rocky substrate, but can handle poorly drained areas as well. It is a host plant to banded skipper butterflies and the seeds are an important food source for many birds and wildlife. As a bonus, it is also highly resistant to deer browsing.

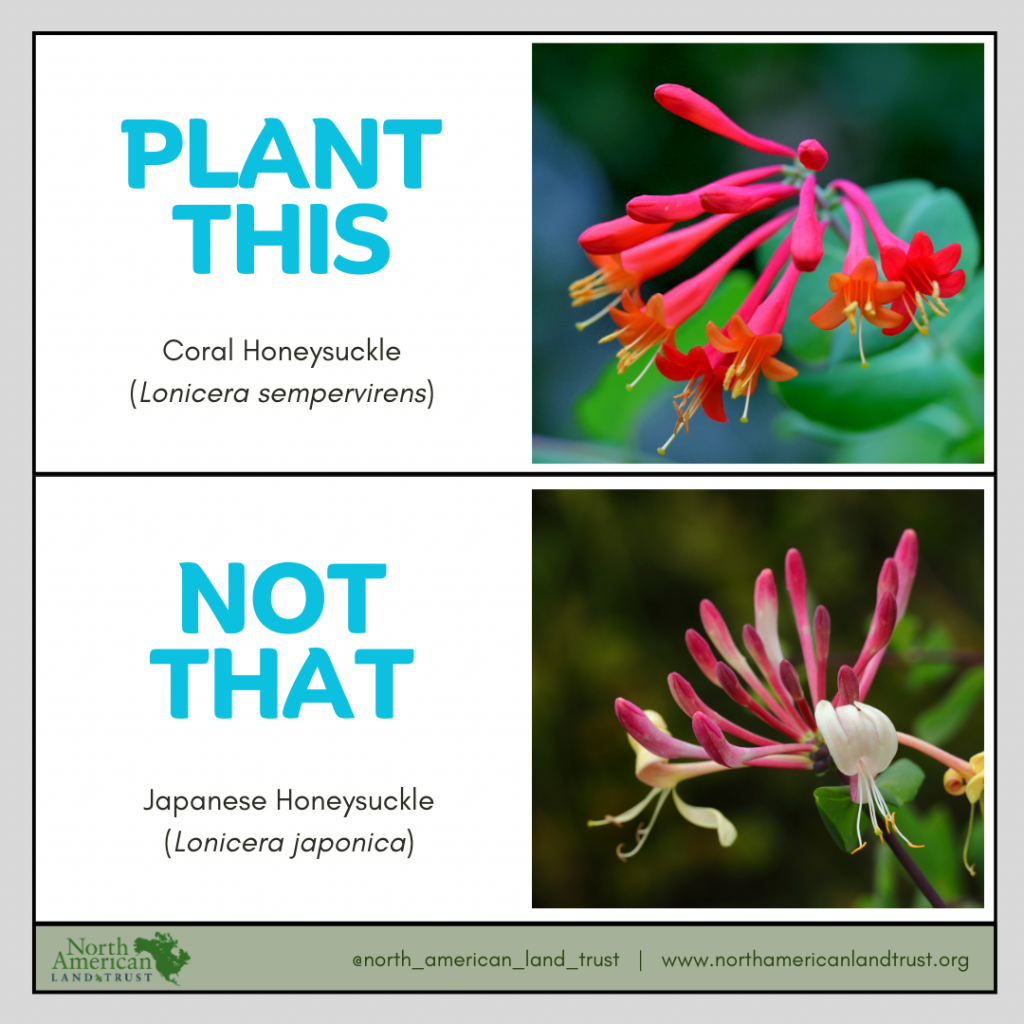

Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) is an introduced woody vine for ornamental use from Japan, intended to control erosion and stabilize banks for highways, however, it unfortunately has a habit of overtaking natural areas, particularly in climbing over trees and along forest floor and crowding out native vegetation. While the flowers are very strongly scented and attractive, our native honeysuckle is much more colorful with the added benefit of attracting hummingbirds!

Coral Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) is a native vining honeysuckle with stunning red tubular flowers and large oval green-blue foliage. It has large red edible fruits and is evergreen, especially in the South. It attracts a variety of bees, butterflies, and the fruits feed a number of wild bird species which spread the seeds in the same way that the invasive honeysuckle is. The foliage is the host plant for the Spring Azure (Celastrina “ladon”) and the Snowberry Clearwing (Hemaris diffinis).

Ajuga, or Bugleweed is a member of the mint family from Europe where it grows as a groundcover. Due to its ability to spread easily, its colorful leaves, and purple flowers, it is a commonly planted groundcover in gardens across the United States. Unfortunately, its success as a groundcover also means that it commonly spreads outside of planted areas, and it is considered an invasive species in Oregon, West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

A great alternative for Ajuga is our native genus Scuttelaria, a native mint with a variety of species for any condition. There are at least 350 species worldwide and many within North America to choose from for the home garden. Scuttelarias have bright purple flowers that are attractive to pollinators, and the foliage feeds the larvae of multiple butterfly and moth species. It is a great pick or substitute for bugleweed in any garden.

Butterfly Bush (Buddleja sp.) has been a “first choice” for those looking to attract pollinators to their yard due to it’s availability, but it is far from the “best choice” for our native butterflies. While it does provide a nectar resource to adult insects, it doesn’t provide food for larvae. It produces an abundance of seed which spreads far and wide into natural areas.

A better choice is a native milkweed (Asclepias sp.) of which there are so many regional choices to choose from. Native milkweeds provide nectar to a variety of insects and also act as a host plant for an insects like the Monarch Butterfly, as well as a number of other insects. There are also a number of other native shrubs and wildflowers that can offer a similar look and structure to Buddleja without having invasive potential. Check out the resources below for more suggestions.

While these plants may not be in your area, send us a message if you would like suggestions for your region. To learn more about eradication of invasive species on your property, improvement of your habitat with native plants, or other habitat management questions, reach out to us at info@nalt.org and www.nalt.org.